Author: Lilian Kaivilu | Producer: Dorothy Okemo

In our blog series “Four tales from Narok County, Kenya” we put the spotlight on the healthcare situation of people living in this district, with a special focus on sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Where there’s little or no money for health, a lonely nurse struggles to serve the 5,000 people in his district and a volunteer with a background in tourism steps in to educate communities on SRH. Without financial support youth centres have to close leaving adolescents with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) to seek help at neighbouring counties’ facilities. Facing a lack of education on sexuality and contraceptives, many young girls are condemned to a life of unprepared motherhood; forced to abandon their education all together. But among all these challenges there are people who fight for better knowledge of SRH Rights and improved access to medicines.

In our previous tales from Narok County, we visited Robert Magero, the nursing officer at Etereti Dispensary, Mark Lari Letoluo, a volunteer health worker in Ololung’a, and the abandoned Narok Youth Resource Centre. The closing of this facility left a gap in sexual and reproductive health education, which goes hand in hand with teenage pregnancies in the county. The following tale from Narok features three young women, who faced teen pregnancy and returned to school after giving birth.

Upon giving birth, many young girls are condemned to a life of unprepared motherhood; forced to abandon their education. For many of their parents, this is the easiest way to usher them into marriage, regardless of their age.

Christine Kereto knows this all too well. At the age of 16, Christine, the youngest in a family of nine, got pregnant and gave birth to twin girls in 2018. To her father, this was the end of her education. He chased her away and wanted her married to the man who got her pregnant. “But I was not ready for marriage. I wanted to continue with my education,” says Christine. Although Christine’s father had already talked with the man responsible for her pregnancy about marrying her, an adamant Christine was focused on resuming school. “I was forcefully married off to the man but after two weeks I escaped in order to go back to school. I have never gone back to the home,” she says.

Fortunately, her mother offered to take care of her children while she continued with her school. One year after giving birth, Christine repeated Standard Seven [last grade before students change to secondary (high) school] in January 2020 and is optimistic of completing and performing well in her primary education. Her elder brother also offered to pay for her school fees. According to Christine, had she known of different contraceptives, her story would be different today.

Life in school wasn’t any better. She was ridiculed by her classmates. As the only mother in her class of 50 students, Christine developed a thick skin. She says her eyes were set on completing her primary education. She is now in Class Eight, awaiting schools reopening in order to sit her Kenya Certificate of Primary Education. She hopes to obtain over 400 out of 500 marks in her final national examination.

Just like Christine, Elizabeth Kisemei gave birth in 2017 while in Standard Seven. The only girl in a family of eight, Elizabeth was forced to skip a whole year in order to take care of her child. She admits that stigma for young mothers is still rife in her community. But this did not stop her from pursuing her dreams. “I wanted to resume school because I thought it was more beneficial than getting married.” Although her father was adamantly against letting her go back to school, her mother was supportive.

Elizabeth, however, says school fees remain a challenge as her parents cannot afford them. With an ailing father, Kisemei’s school fees are in arrears but this, she says, will not deter her from achieving her goals.

The young mother says nothing prepared her for the birth process. “I never had access to antenatal clinics. I even did not know what to expect during labour,” says Elizabeth, who aspires to be a doctor. Prior to getting pregnant, Elizabeth says she had no information on safe sex or use of contraceptives. She is now back to school and in Standard Eight, ready to sit het final examinations once school sessions resume.

According to Girls Not Brides, child marriages undermine the lives and future of about 12 million girls worldwide every year. This means globally, 23 girls under the age of 18 are married off every minute. Most of the time, the children involved in these marriages do not have a say on the matter.

Judith Sinantei refused to be part of the statistics of girls being married before their 18th birthday. She is the first born in her family. As such, she was seen as the only hope in her family and expected to finish school and get a job to support them. She got pregnant while in Form One, the second year of secondary school. “My parents saw my pregnancy as a disappointment as it would derail me from achieving my goals. They were hoping that I would be the help for my mother and my younger siblings,” she says. Judith resumed school in January this year. She is now a Form Two student.

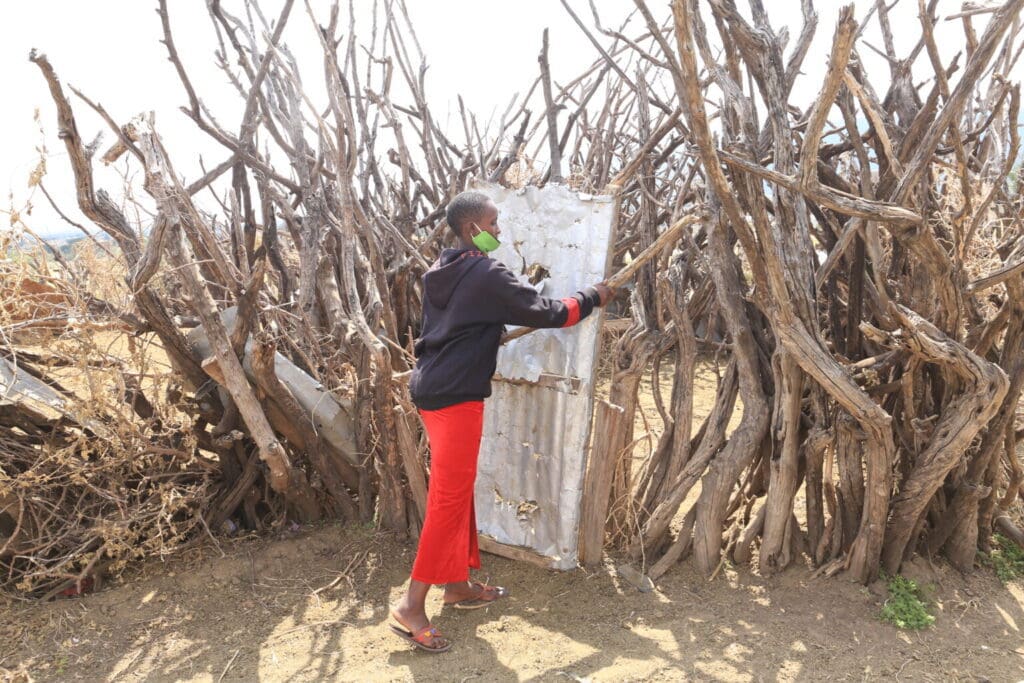

Mary Silantoi Sarafina, a volunteer Children Officer in Narok County says many girls are lured into premarital and unsafe sex by men who promise them sanitary towels. For the average girl or women in the village sanitary towels are unaffordable. A pack of eight usually retails for about $6 and if their parents are living below a dollar a day and the girls are in school and hence not working, buying sanitary towels is not a priority. Men use this in the rural setting to lure girls with money for sex, which will then provide them with the resources they need to buy sanitary towels to avoid the shame and embarrassment they have to face with staining of clothes or having to stay at home during their menses. The result is unwanted teenage pregnancies. According to Sarafina, parents and the local administration ought to play their role to ensure that girls are well aware of their rights and have access to sanitary towels. But since many school going girls depended on menstrual product donations through their schools, there is now a gap in supply as schools are closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to fill this gap, Sarafina distributes sanitary pads to girls in the area.*

*On 15 January 2021 the Ministry of Education in Kenya set aside Ksh470 million to ensure sanitary towels to school girls across the country. The Minister for Education, Prof. George Magoha, mentioned that the distribution of sanitary pads would start on 18 January 2021.

To prevent teenage pregnancies in the long term, the county government must provide enough money for special education programs, keep up the access to sanitary pads, contraceptives, and other sexual health commodities.

But as highlighted in our “Four Tales from Narok County”-series, the lack of money (and priorities) can be noticed everywhere: There are not enough professionally trained healthcare workers as we highlighted in our stories about a struggling nurse and a health volunteer with a background in tourism. Also, youth centres, the former go-to-point for adolescents, have been closed due to lack of funding, leaving girls and boys with no knowledge on—and access to— contraceptives and STD commodities. It needs organisations like MeTA, supported by Health Action International, to empower community members to stand up for their rights and advocate for better access to SRH education and commodities.

At the end of 2015, Health Action International (HAI) teamed up with Amref Health Africa, the African Centre for Global Health and Social Transformation (ACHEST), Wemos and the Dutch Ministry for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation to form the Health Systems Advocacy (HSA) Partnership, which ran until the end of 2020. Throughout this five-year programme, the HSA Partners contributed to stronger health systems that enabled people in Sub-Saharan Africa to equitably access high-quality Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) commodities and services. As part of our work on SRH, we contributed to capacity building by equipping civil society actors and health stewards with needed knowledge, technical skills and tools to develop and implement evidence-based advocacy strategies. Our work in this field drew upon our research and advocacy expertise. In collaboration with our in-country partners, HEPS Uganda, Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA) Zambia and MeTA Kenya, we studied the price, availability, and affordability of SRHC in facilities across Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania. These findings formed the basis of our advocacy work with our in-country partners. Our blog series “Four Tales from Narok County” shows that there is more work to be done with our in-country partners. Therefore, Health Action International is looking for new funding opportunities to pursue the collaboration with multi-stakeholder platforms and grassroot organisations in their fight for SRH rights.