Health Action International Presents “Minutes to Die” at the Dutch Global Health Film Festival

by BIRTE BOGATZ, Communications Advisor

How do you measure the burden of a health emergency? We often tend to do that by counting—the dead, the disabled, the dollars to be paid for treatment. We end up with numbers, which are certainly very valuable because they enable us to make our point when trying to change health policy. The higher the numbers, the higher the priority on the global health agenda—in many cases, it’s as simple as that. But sometimes those numbers on paper blind us to what lies behind them: The individual fates.

How do you measure the burden of a health emergency? We often tend to do that by counting—the dead, the disabled, the dollars to be paid for treatment. We end up with numbers, which are certainly very valuable because they enable us to make our point when trying to change health policy. The higher the numbers, the higher the priority on the global health agenda—in many cases, it’s as simple as that. But sometimes those numbers on paper blind us to what lies behind them: The individual fates.

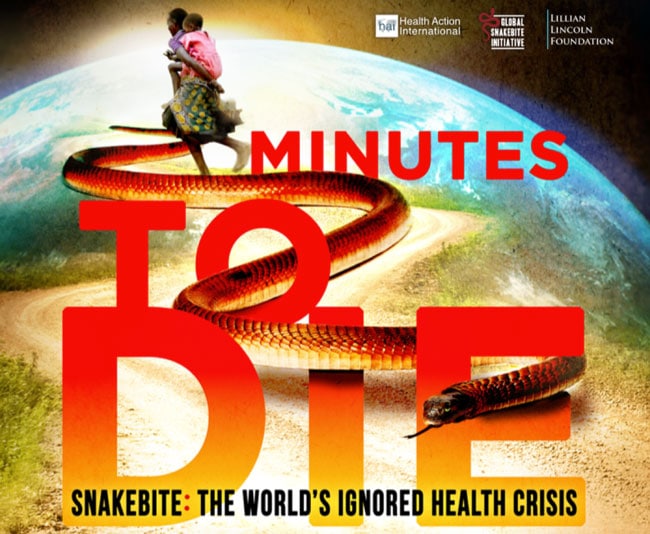

Numbers don’t tell stories, but the American film director, James Reid, does. With his documentary, “Minutes to Die”, funded by the Lillian Lincoln Foundation, James gives snakebite victims a voice—and a powerful advocacy tool.

In 2016, an excerpt of the film shown during a World Health Assembly side event on snakebite shook the audience and helped lay the foundation to get snakebite envenoming back on World Health Organization’s (WHO) priority list of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

Now, one year later, not only has the WHO reinstated snakebite as a high-priority NTD; James’s film has gone through its final cut. Health Action International (HAI) is thrilled to present it at the Dutch Global Health Film Festival on 28 October. The screening will be followed by a panel discussion with snakebite experts.

We spoke to James, who will take part in the panel discussion, ahead of the Festival to find out what compelled him to make the film and what he discovered while making it.

Next thing we knew, we were on a plane.

HAI: James, you live in San Francisco, far away from those countries where lives are at stake due to snakebite. What got you into doing this film and covering this topic?

James Reid: I grew up in California, always hearing news stories of people getting bitten by a rattlesnake. They get to a hospital, there is ample supply of antivenom and they survive. They’re typically the lucky ones in this world. We first met Dr Matt Lewin, a local emergency room physician and field medicine expert with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Dr Lewin had been developing a field antidote for rural snakebite victims in the tropics, so that a bite victim could administer the drug immediately following a bite to slow some of the effects of the venom. It sounded fascinating, but all we knew was that no more than five people die in the United States or Australia in any given year. When we looked into the magnitude of the problem, the numbers and stories were staggering. More than anything, I was surprised no one had ever told the story of the plight of these voiceless victims. Next thing we knew, we were on a plane.

There wasn’t a soul who couldn’t steer us to someone they knew who had been bitten.

HAI: Along with your film crew, you have spoken to snakebite victims in remote areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, India and Papua New Guinea. How was this experience and how did you find those people who’ve never had the opportunity to tell their story, before?

James Reid: What shocked us more than anything was how effortless it was to find victims and their desperation to tell their story to the world. We had contacts on the ground that went in search of victim stories before we arrived. All you needed to do was to ask anyone in any village if they knew someone who was bitten or died. There wasn’t a soul who couldn’t steer us to someone they knew. All victims talked of the daily fears of a snakebite, which tends to outweigh fears of contracting malaria or tuberculosis in many cases. No matter where we filmed, everyone had a connection. Everyone begged for the story to be spread.

The stories will be etched in our minds forever.

HAI: Those fates you came across are staggering: Parents losing their children, maimed victims being discriminated against and excluded, families having to do without their bread winners and facing widespread destitution. We don’t want to pre-empt the film, but if you could tell us one story that particularly stuck with you and is emblematic of the problem, which would it be?

James Reid: From the victim to the family of a victim, everyone had a heart-wrenching story of their long journey to reach a hospital, and many times the hospital was without antivenom. Every farmer or herder has sold land, animals or personal possessions to pay for treatment and these dollar-a-day earners were left with nothing and even less hope. Meeting a Kenyan family who lost a daughter to a cobra bite minutes before her sister was also bitten will be etched in our minds forever. Imagine having one daughter buried under a cross in the yard, while the surviving sister is being held by her parents because she requires around-the-clock care. She can’t walk, her hand is deformed and she is blind.

It is really easy to be the ones to make change.

HAI: In June 2017, snakebite envenoming was adopted as a priority NTD by the WHO, making it significant for the global health community. In addition to that, is there something the public could do after watching your film?

James Reid: The WHO took an incredible step listing snakebite as a neglected tropical disease. But that classification is just the beginning. Funding by world donors and support from governments in snakebite-endemic countries is critical. Snakebite is not like Ebola, which became a household name and received instant attention and funding. No one knows of the snakebite crisis and that’s why each and every one of us who believes this should not be happening needs to be the one to share the story with the world.

The film is a tool to bring awareness to this ignored way to die. Screening the film is one way to get NGOs, civil society, companies and organisations to give the voiceless a voice. Our website, www.minutestodie.com, is an important starting point for anyone in this world who believes this crisis should no longer be ignored. Sharing (through social media) short informative videos on the issue found on our site gives anyone the chance to do something to raise the profile. We encourage people to donate to one of several “on-the-ground” snakebite projects that will bring real change to parts of India and Sub-Saharan Africa. The projects are led by experts who have historically received little to no funding. It is really easy to be the ones to make change.

HAI: Thank you for the interview, James! We are really looking forward to seeing you and watching your film at the Dutch Global Health Film Festival.

The Dutch Global Health Film Festival takes place on 28 October, 2017, from 2:30–9:30 pm, in Filmtheater ’t Hoogt in Utrecht. Tickets are already available. The screening of “Minutes to Die” will be hosted by HAI and followed by a panel discussion with film director, James Reid, and experts on snakebite, including Dr David Williams, chief executive officer of the Global Snakebite Initiative and Ben Waldmann, HAI’s programme manager for snakebite.