This piece was written by guest contributer Denis Kibira, Executive Director of our partners, HEPS-Uganda.

Late January 2020 in my hotel room in Mombasa on the side-lines of a Health Systems Advocacy Partnership meeting led by Health Action International, I was gripped by the attention that the international media had given to a fast spreading new form of coronavirus in the city of Wuhan in China. Wuhan had been put on total lockdown. It seemed far off, incomprehensible and obscure, but in less than a month’s time, the global community was in panic.

The COVID-19 pandemic caught the world off-guard and many countries have been brought to their knees. Countries have closed their borders, schools, religious and all social institutions, businesses, restaurants, markets and offices. Many countries have placed their citizens and services under lockdown except for essential services, such as food and emergency hospital services. In Uganda, the first Presidential directives to safeguard against COVID-19 were delivered on 18 March 2020, among them the closure of schools, religious and social gatherings. Up to 50 directives, including lockdown of both public and private transport, followed later. The closure of international and domestic travel and businesses has disrupted industrial production, global supply chains and service delivery. This has had adverse effects on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services.

For example, on 28 March 2020, Reuters reported a looming shortage of condoms due to the closure the world’s largest condom manufacturer Malaysia Karex Bhd, responsible for 20% of the world’s condom production. This will certainly affect contraceptive programmes worldwide.

The International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) announced the closure of more than 5000 of its member association SRH clinics and care centres across the world, while others scaled down their services. Uganda is one of the countries that reported the closure of over than 100 of these clinics. This is expected to impact the lives of many. In a statement, IPPF warned that up to 9.5 million vulnerable girls and women risk losing access to contraception and safe abortion services in 2020.

The closure of non-emergency services and transport restrictions imply that, suddenly, condoms, contraceptive pills and many SRH commodities and services have been deemed non-essential and have therefore become a luxury. Family planning, antenatal care and deliveries at health facilities are therefore not readily accessible. During a televised Easter Sunday sermon, the Archbishop of the Church of Uganda, Bishop Stephen Kazimba Mugalu, warned of an upsurge in unwanted pregnancies during the lockdown. He advised that women in particular take charge and access family planning services. However, this will be a challenge if facilities are not open, do not have the services or are unreachable to girls and women.

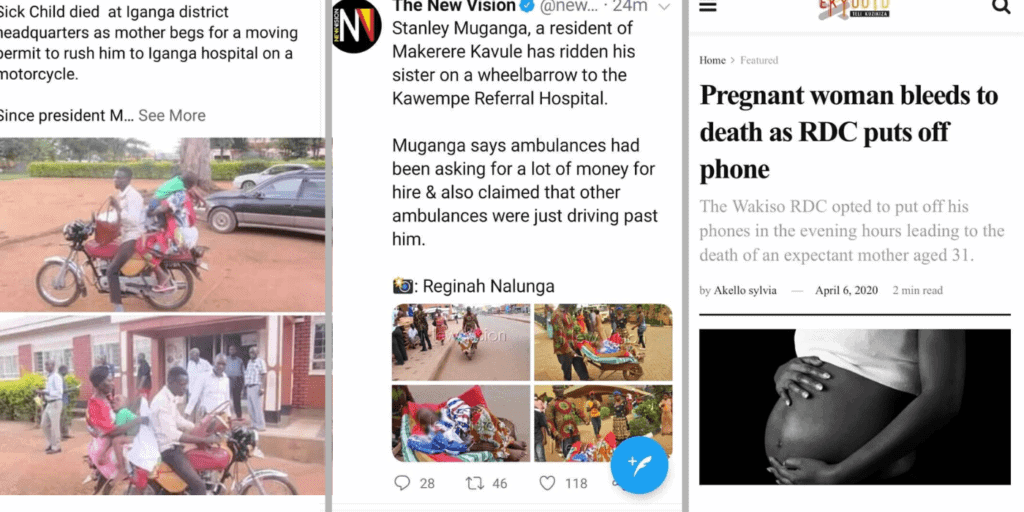

One of the Presidential directives on COVID-19 is a requirement to acquire permission from the President’s representative in the district, the Resident District Commissioner (RDC), for any emergency travel. This is not been practical or reliable as the RDC’s offices are not easily accessible to majority of the population. Several pregnant women are reported to have died or lost their children in the process of reaching health facilities for care. An activist first highlighted this challenge a few days into the lockdown when he posted a picture of community members helping a woman to deliver by the roadside after she failed to reach the hospital. Several disturbing reports came through later, including the much publicised case of Scovia Nakawooya. There are many such cases which do not receive media attention.

Police authorities and civil society practitioners have reported an upsurge in domestic violence in which a number of women have lost their lives during the lockdown. Lockdowns increase inequality and vulnerabilities of the poor, particularly those that live on a day’s earnings, which may spur violence. Therefore implementation of lockdown measures should take into account social fabrics of society.

The precautionary measures to reduce the spread of coronavirus should be implemented in such a manner to minimise inequality and unintended impact on SRH. It is illogical to save the population from COVID-19 and yet expose it to fatalities to which government and partners have made heavy investments over several years. The government should devise measures to ensure that reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services remain readily accessible and ensure the functioning of community systems to ensure adequate support for especially vulnerable women and girls.