Barbara Mintzes, Les Toop and Dee Mangin | 2010 | Download PDF

Original citation: Mintzes, B., Troop, L., & Mangin, D. 2010, ‘Promotion to Consumers: Responding to Patient Requests for Advertised Medicines’, in Mintzes, B., Mangin, D., & Hayes, L. (eds.) Understanding and Responding to Pharmaceutical Promotion: A practical guide, Health Action International, Amsterdam, pp. 81-104.

Since the 1990s, pharmaceutical manufacturers have increasingly begun to promote their medicines directly to the public. This marketing has been shown to lead to more prescriptions and therefore more sales of medicines (Gilbody, 2005). It also has profound implications for the public perception of medicines and the relationship between patients and health professionals.

Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) of prescription medicines through television, radio, magazines, newspapers and billboards is legal in only two countries, New Zealand and the US. In countries that do not allow advertising of prescription medicines, however, other forms of direct and indirect promotion to the public often occur. These include industry- sponsored disease awareness campaigns, patient compliance and disease management programmes, promotional material on the Internet and sponsored television ‘infomercials’. Some countries allow unbranded advertising campaigns that prompt consumers to “ask your doctor” for a new treatment. Disguised promotion, in the form of promotional press and video news releases and resultant news coverage, is also common. Advertising campaigns targeting the public have thus become a reality in many countries despite their sometimes questionable legal status.

In countries with well-enforced laws governing prescription-only status, people who view advertisements for a prescription-only medicine cannot buy the product directly; they must first ask a physician for a prescription. In lower-income countries, prescription-only status is often poorly enforced, and a person can generally buy any medicine directly without first seeing a doctor. In these countries, it is pharmacists who are likely to be most affected by patient requests for advertised medicines.

All health professionals face the dilemma of how to respond to patient requests for advertised medicines. Patient requests are sometimes based on inaccurate beliefs about a medicine’s effects or appropriateness for their own situation. Patients can also be forceful. This can create a tension between evidence-based decision-making and patient-centred care. Misunderstandings on both sides may interfere with appropriate care. It is important for health professionals to understand the mechanisms behind promotion-influenced patient requests and develop appropriate responses.

The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to the research evidence on consumer-directed advertising of medicines and the way that promotion targeting the general public affects prescribing decisions. The chapter also provides some guidance on ways to respond to patient requests for advertised medicines.

Aims of this chapter

At the end of the session based on this chapter, you should be able to:

- Discuss, with examples, how promotion of medicines to the public has been shown to affect patient care;

- Describe the range of techniques used to promote medicines to consumers;

- Discuss strategies you can employ when responding to requests from patients driven by promotional messages.

Promotion’s effects on behaviour

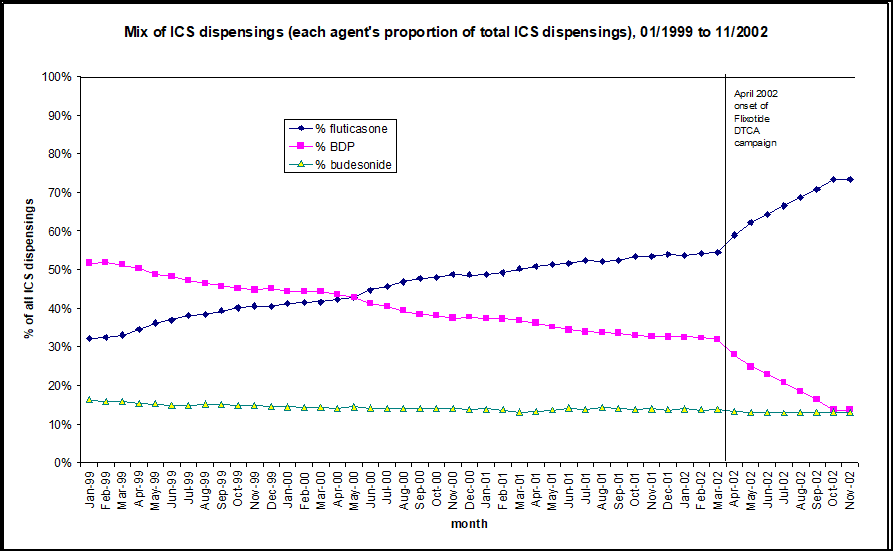

Do patients request advertised medicines from their doctors and do doctors prescribe requested medicines? Research from both New Zealand and the US suggests that advertising of medicines does affect prescribing and use. Figure 1 shows the rates of prescribing for two types of asthma inhalers before and after a DTCA campaign for one of the inhalers, Flixotide (fluticasone). The graph shows that many patients who had been prescribed beclamethasone switched to fluticasone. These are two different types of corticosteroids used to prevent asthma attacks. At the time of this campaign, Flixotide (fluticasone) was more expensive than beclamethasone. It is no more effective at equivalent doses, but is more potent per microgramme, which can be a problem when switching, especially with treatment of children. This switch in medication resulted in expenditure of nearly US$3 million more than if the less expensive inhaler had been used.

Figure 1: DTCA leads to substitution of a more expensive steroid inhaler: dispensing data from New Zealand’s public drug plan (PHARMAC)

ICS = inhaled corticosteroids, BDP = beclamethasone dipropionate

(Source: PHARMAC; In Toop, 2003)

There is also evidence from the US that advertising affects the choice of medicine that is used. For example, a US analysis of a large administrative database of prescriptions found that more patients began use of an advertised brand of proton pump inhibitor (a medicine for gastric reflux and ulcers) than a similarly effective non-advertised brand when advertising levels were high and when their insurance plan covered most of the cost of their medicines (Hansen, 2005). This study suggests that when consumers are not paying directly for their medicines they are especially likely to be influenced by advertising.

The research arm of the US Congress, the US General Accounting Office, estimated in 2002 that eight million Americans requested and received medicines in response to DTCA each year, based on consumer surveys (Heinrich, 2002). New Zealand consumer surveys show proportionally similar results (Toop, 2003). In other words, advertising of medicines does lead directly to patient requests that result in increased prescription rates and rates of use.

How does advertising to the public affect prescribing?

If a prescription medicine is advertised on television in New Zealand or the US, the viewer cannot simply go to the store and buy it, as they might buy an advertised pair of shoes or a soft drink. Viewers must ask their doctors for a prescription. However, prescriptions are medical treatments with inherent dangers, not consumer products, and doctors are legally responsible for the prescriptions they provide. So does advertising really affect prescribing decisions?

Two prospective studies in doctors’ offices have compared consultations in which patients requested advertised medicines with consultations in which they did not. One was a comparison between patients of family doctors in Sacramento, US where DTCA is legal, and Vancouver, Canada, where DTCA is illegal but there is some cross-border exposure from the US (Mintzes, 2003). The other was an experimental study that compared consultations in which actresses pretending to be patients (‘standardised patients’) did and did not request an advertised medicine (Kravitz, 2005).

In the first study, patients filled in a questionnaire in the waiting room, which was matched with a physician questionnaire following the consultation. The physicians reported on all new prescriptions they had provided and any that the patient had requested. US patients and those with more self-reported exposure to DTCA were more likely to request an advertised medicine. Physicians prescribed three-quarters of requested DTCA medicines. However, they were often ambivalent about these decisions; they judged half of new prescriptions for requested advertised medicines to be only “possible” or “unlikely” choices for othersimilar patients. In contrast, physicians judged only one out of eight prescriptions for medicines not requested by patients to be “possible” or “unlikely” choices for other similar patients.

In the second study, the ‘standardised patients’ made nearly 300 unannounced visits to family doctors in three cities (Kravitz, 2005). The visits were randomly allocated to several scenarios. The ‘patients’ either described symptoms of clinical depression or of an ‘adjustment disorder’ – a normal response to a stressful life problem, moving to a new city and being unemployed. For each condition, the ‘patient’ either asked for a prescription for the antidepressant Paxil (paroxetine), which was advertised on television, for an antidepressant in general, or did not request a medicine.

The doctors prescribed antidepressants in just over half of the visits in which Paxil was requested for both clinical depression and adjustment disorder. In other words, if a patient requested this antidepressant, physicians were equally likely to provide an antidepressant prescription whether or not the patient had depression, the condition the medicine has been tested for and is approved to treat. ‘Patients’ with adjustment disorder who requested Paxil were 13 times as likely to receive an antidepressant prescription as those who did not request a medicine. The ‘adjustment disorder’ scenario was a normal response to a stressful life event; it should not have been treated with a medicine. Although these were actors, the study raises strong concerns about the negative effects of DTCA on prescribing quality.

In this study, those with a depression diagnosis were also more likely to receive standard follow-up care (i.e. care that was consistent with treatment guidelines for depression) if they either requested Paxil or asked generally for an antidepressant. A brand-specific request did not increase the rate at which they received this care. They were less likely to receive this level of care, which involved repeat visits and either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, if they did not ask for a medicine. However, after controlling for whether or not they received a prescription, there was no difference in whether ‘patients’ with adjustment disorder or depression received follow-up care (Epstein, 2007).

These studies suggest that advertising affects prescribing, both because doctors sometimes prescribe and pharmacists provide medicines they might not prescribe otherwise, and because if a patient asks for a medicine, the doctor is likely to prescribe it. This is consistent with other research showing that even in the absence of advertising, doctors are more likely to prescribe a medicine if they believe the patient wants one (Britten, 1997; Cockburn, 1997).

Do other types of promotion affect medicine use?

In many countries, including both those where DTCA is and is not allowed, companies sometimes run unbranded disease awareness or ‘help-seeking’ promotional campaigns. These discuss symptoms of a condition and suggest that viewers or readers “ask your doctor” about a new treatment.

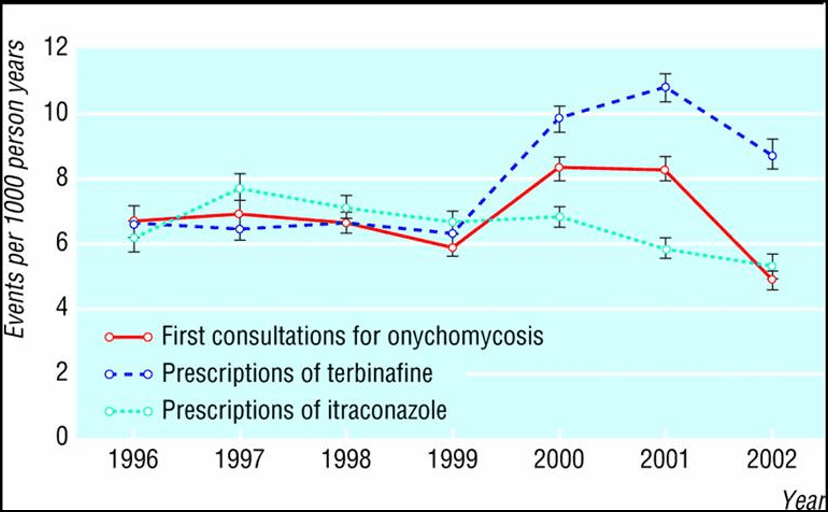

In the Netherlands, Novartis, manufacturer of the antifungal medicine Lamisil (terbinafine) ran a televised advertising campaign about toenail fungus in 2000 and 2001. The brand name was not mentioned, but the commercials strongly suggested asking your doctor for treatment for toenail fungus. An analysis of effects on consultations and prescribing was carried out in a Dutch primary care research database covering 150 physicians’ practices and more than 470,000 patients (‘t Jong, 2004). As shown in the graph, the prescribing rate for this medicine doubled after the campaign started. Rates of first consultations also went up during the campaign, falling again afterwards.

Figure 2: An analysis of effects on consultations and prescribing of a disease awareness promotional campaign in the Netherlands

(Source: ‘t Jong, GW et al., 2004)

The authors of this study raised concerns about the effects of these advertisements on the workload of family doctors. They felt that the time spent with patients with this minor and mainly cosmetic condition took time away from patients with more serious health problems. There are two other concerns. This is an expensive treatment of limited long-term effectiveness. In a large randomised, controlled trial, only 25% of patients were completely cured at 18 months (Warshaw, 2005). Additionally, there is a rare but serious risk of liver toxicity (‘t Jong, 2004).

In an earlier US study, Basara (1996) also found that an unbranded advertising campaign for Imitrex (sumatriptan) a migraine medicine, led to more prescriptions. These analyses show that even when a brand name is not mentioned, companies can successfully promote sales of a prescription medicine through advertising that tells the public to go to their doctor to seek treatment.

Since

2005, Australian disease awareness advertisements can legally direct viewers to

branded Internet advertising. This provision was introduced within a bilateral

trade agreement with the US (Australian Govt., DFAT, 2006). As of mid-2007, the

effect of this change on attitudes to medicines, medicine use, health or costs

has not been studied.

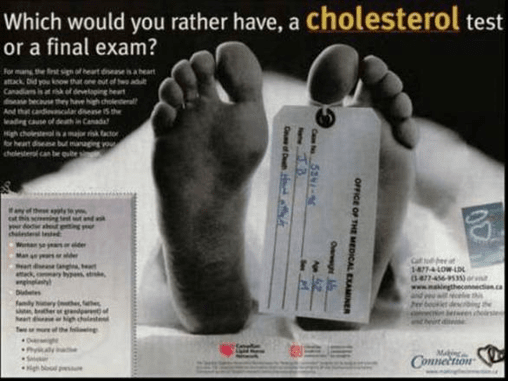

Figure 3: Canadian ‘toe-tag’ advertisement, funded by the manufacturer of a leading cholesterol-lowering medicine

Fear of death used to sell a medicine – even with no brand name mentioned

World Health Organization staff raised concerns in a letter to the UK journal The Lancet about a disease awareness advertising campaign in France promoting cholesterol testing, by the manufacturer of a leading brand, Lipitor (atorvastatin) (Quick, 2003). Print advertisements showed the tagged toe of a corpse. The image below is from a similar Canadian campaign by the same company. The authors of The Lancet letter believed that the advertisements could cause undue anxiety, failed to convey the importance of other risk factors for heart disease, such as smoking, obesity or a sedentary lifestyle, and “contained misleading statements and omissions likely to induce medically unjustifiable drug use or to give rise to undue risks.”

(Advertisement from: http://www.health-heart.org/final_exam.jpg)

How well does advertising inform the public about available medicines?

Advertised medicines are mainly new, expensive treatments for regular or intermittent long-term use among large population groups. Cheaper, generic, off-patent medicines are rarely, if ever, advertised to the public.

One of the main claims made for medicines’ advertising is that it informs the public about the newest available medicines. This is true. What is debatable is whether promoting widespread use of these newest medicines is beneficial. When it comes to medicines, newer is not necessarily better. Companies spent more than US$800 million advertising just five medicines to the US public in 2004 (see Table 1). None were ‘breakthrough’ medicines meeting important previously unmet health needs. For example, Nexium (esomeprazole) – the medicine with the top advertising budget in 2004 – is simply one of the two enantiomers or isomers of the racemic mixture which makes up omeprazole, a medicine for which less costly generic equivalents are available. (An enantiomer or isomer of a chemical compound has the same molecular formula but a different structural configuration in space.) Refining the isomer allowed separate patenting, but unsurprisingly Nexium (esomeprazole) is no more effective than omeprazole at equivalent doses (Therapeutics Initiative, 2002).

Table 1: Five top medicines by US DTCA spending January – November 2004

| Medicine | Indication | Spending (US$ millions) |

| Nexium (esomeprazole) | Ulcer/reflux | $226.0 |

| Crestor (rosuvastatin) | Lipid lowering | $193.2 |

| Cialis (tadalafil) | Impotence | $152.6 |

| Levitra (vardenafil) | Impotence | $142.0 |

| Zelnorm (tegaserod) | Irritable bowel syndrome | $122.0 |

| Total – top 5 | $835.8 |

(Source: Arnold, 2005)

Of the four other medicines in Table 1, three have been subject to safety advisories, and one, Zelnorm (tegaserod) was withdrawn from the US market in March 2007 due to increased risks of heart attack, angina and stroke (US FDA, 2007). There is evidence of greater risks of rhabdomyolysis, a muscle-wasting disorder, with Crestor (rosuvastatin) than other medicines in the class (Public Citizen, 2003). Cialis (tadalafil) and Levitra (vardenafil) are similar to Viagra (sildenafil) and all can cause visual abnormalities (US FDA, 2005).

The choice to intensively advertise a specific brand is a marketing decision, based on the likely return on investment (Arnold, 2005). It is not a public health decision. In these examples, prescriptions stimulated by intensive advertising may not be the best answer for individual patients, either because a more cost-effective or safer alternative exists or because a non-drug solution might be a better option, especially for mild problems.

There

is some evidence that people who are exposed to more advertising for medicines

for conditions that are affected by lifestyle are less likely to pursue healthy

activities. Iizuka and Zhe Jin (2005) compared results of a national US health

survey with advertising spending for medicines for diabetes, high cholesterol,

obesity and hypertension. They found that when there was more advertising for

medicines for these conditions, people were less likely to report that they had

regular, moderate exercise. This is consistent with a content analysis of US

television advertising, which found that none of the advertisements portrayed

lifestyle change as an alternative to taking the product and 18% conveyed the

message that lifestyle change was insufficient (Frosch, 2007).

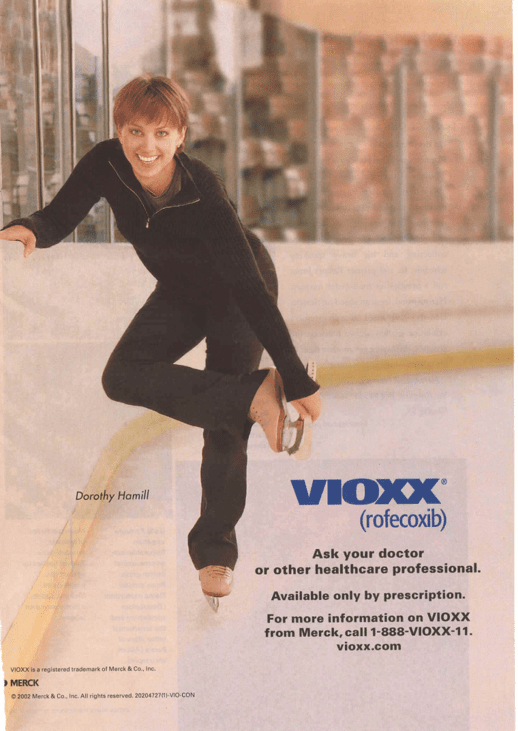

Box 1: Advertising of the arthritis medicine Vioxx (rofecoxib)

| Between 1999 and 2004, one of the most heavily advertised medicines was Vioxx(rofecoxib), an arthritis treatment. The medicine’s manufacturer, Merck, spent more than US$550 million advertising this product to the US public (Topol, 2004). In 2000, more was spent on advertisements for Vioxx (rofecoxib) than on Pepsi-Cola advertisements (Findlay, 2001). Over 80 million people took the medicine worldwide. It was withdrawn from the market in 2004 when it was found to increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes. On the basis of clinical trial findings and population patterns of use, senior US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) official David Graham estimated that between 88,000 and 140,000 extra heart attacks in the US were due to the use of Vioxx (rofecoxib) (Graham, 2005). Merck’s intensive advertising of this medicine is controversial not only because of the evidence of serious harm, but because the first major study to show an increased risk of heart attacks, the VIGOR trial, was published in late 2000, four years before advertising stopped (Bombardier, 2000). Although Vioxx (rofecoxib) is the highest profile medicine to feature in DTCA and later be withdrawn for safety reasons, it was not the first or the last. Other examples include the cholesterol-lowering medicine Baycol (cerivastatin), the diabetes medicine Rezulin (troglitazone) and the irritable bowel syndrome medicine for women Zelnorm (tegaserod). |

Figure 4. Advertisement for Vioxx

This is a 2002 US magazine advertisement for rofecoxib (Vioxx) The woman featured in the photo is Dorothy Hamill, who won an Olympic gold medal in 1976.

(Advertisement from: www.todaysseniorsnetwork.com)

Making ‘newer’ seem ‘better’

Advertising campaigns are usually most intensive in the first few years of a medicine’s marketing life. This is also when less is known about a medicine’s rare or longer-term effects. An analysis of all medicines approved in the US between 1975 and 1999 found that half of medicine safety withdrawals occurred within the first two years a medicine was marketed (Lasser, 2002). In total, one in five new medicines received ‘black box’ safety warnings or was withdrawn because of serious risks.

There is good reason to be cautious in prescribing or using a new medicine when an acceptable treatment is already available. The implied message in advertising is very different, however. Frosch and colleagues’ (2007) content analysis of television advertising in the US found that more than half – 58% – presented the medicine as a breakthrough.

Education or marketing?

How well does advertising inform the public about medicines’ benefits, risks and contribution to therapy? In 2000, US researchers published an analysis of more than 300 magazine advertisements published over ten years for the presence or absence of key information needed for informed treatment choice (Bell, 2000). They found that the name and indication (approved use) of the medicine were almost always stated but other necessary information was often missing:

- 90% failed to state the likelihood of treatment success;

- 80% made no mention of other helpful activities, like diet or exercise;

- 70% did not mention causes or risk factors for the treated condition;

- 70% failed to mention any other possible treatments;

- 60% omitted any information as to how the medicine works.

The authors did not examine the accuracy, completeness or relevance of information that was provided, only whether it was present or absent.

Figure 5. Advertisement for a sleeping pill

This is an advertisement for the sleeping pill Ambien CR (zolpidem), offering a free trial of the medicine, which is, in fact, a drug of dependency. When considering the educational merits of this advertisement, one should ask what it says about the likelihood of treatment success (proportion of people helped and/or how much more sleep they get); other helpful activities; causes or risk factors for insomnia; any other possible treatments; or how the medicine works.

(Advertisement from Good Housekeeping magazine, April, 2007.)

Financial incentives to use a specific medicine

Another study of US magazine advertisements appearing in ten consumer magazines over a one-year period found that nearly 9 out of 10 “described the benefits of a medication in vague, qualitative terms” and failed to provide any evidence to support claims (Woloshin, 2001). Nearly one-quarter offered financial incentives to use the medicine, such as free trial offers. In a survey of 263 older Americans in the state of Kansas, many of whom were low-income, nearly half said that they would phone a number listed in an advertisement if a discount coupon or free sample was offered (Marinac, 2004). In contrast, without the mention of a discount, only 1 in 9 believed they would make the phone call. The WHO Ethical Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion recommend against the use of financial incentives to influence prescribing decisions (WHO, 1988).

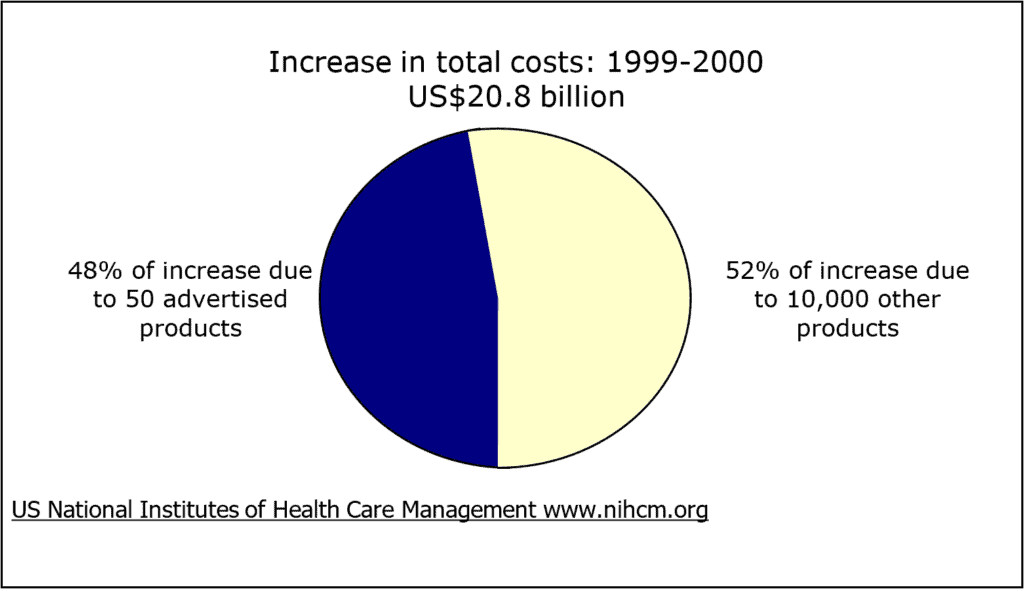

Effects on health-care costs

In 2000, over 95% of spending on advertising was on 50 medicines. Nearly one-third of total US retail prescription medicine costs went toward these 50 brands, or US$41 billion. These same medicines were responsible for more than half of the increase in retail spending between 1999 and 2000 (Findlay, 2001).

Figure 6: Effects on costs of medicines sold in US pharmacies

(Source: Findlay, 2001)

Unrealistic public understanding of safeguards

In two national US FDA surveys of public attitudes and responses to advertising, more than a quarter of consumers thought that only the safest medicines could be advertised to the public (Aikin, 2004). In a California survey, 4 out of 10 people thought only completely safe medicines could be advertised on television (Bell, 1999). Neither statement was true: Any licensed medicine may be advertised to the public. These survey findings suggest that a considerable minority of people mistakenly believe that they are better protected by regulation than is the case.

What is left out is as important as what is said

Whether it occurs in an environment where advertising of prescription medicines is legal or in the form of unbranded promotional messages where advertising is illegal, certain messages – and certain omissions – can be expected from pharmaceutical advertising. The main messages are that a person’s problem is likely to be serious and that a new medicine exists that can help. The images of treatment success usually suggest that the medicine works 100% of the time. Efficacy is thus oversold. In contrast, known and unknown risks and harms are generally omitted or minimised.

Where people see pharmaceutical advertisements on television each day, they hear the message repeatedly to “ask your doctor” for a new medicine that may help you. They also get the message, again and again, that a medicine may be a solution to their problems. Even if a person does not consciously think that there is ‘a pill for every ill’, seeing the message every day can lead to a shift in their understanding of medicines.

Does DTCA affect the doctor-patient relationship?

The messages in advertising are sometimes inconsistent with a doctor’s recommendations for treatment. As one New Zealand doctor explains, this can create disharmony: “I find that it [advertising] can be a nuisance as it creates doubts in patients’ minds about the efficacy of the medication they may already be on.” (Toop, 2003).

Another New Zealand physician, responding to the same survey, believes that sometimes advertising can lead to frustrations and other times it can result in a useful discussion:

“Although I always resist DTCA generated requests to initiate or change medications, these patients simply go to another practitioner (in the same practice!), who gives them anything they ask for. I spend a great deal of time explaining the evidence-based option, the non-drug-based options and the options that will lead to better outcomes at lower doses. I don’t know why I waste my breath! …Very rarely DTC-generated consultations to switch from brown to pink to red inhalers have alerted me to existing poor compliance/poor inhaler technique and even more rarely, the patient has taken on board the messages about improving technique and compliance.” (Anon., in Toop, 2003).

In a California survey, patients were asked how they would react if their physician refused to prescribe a DTCA medicine they requested (Bell, 1999). Nearly half said they would feel disappointed, one-quarter would try to change the physician’s mind and one-quarter would go to another doctor for a prescription.

How should health professionals respond to patient requests for advertised medicines?

If a patient is convinced that an advertised medicine may help him or her, especially with a problem that has been difficult to treat, it can be tempting to simply ‘give it a try’. This is the path of least resistance: The patient has what he or she wants, the health professional has listened and has appeared to be helpful.

It is important to remember that some medicines are classified as prescription-only because they have greater potential for harm than other medicines. Writing a prescription is one of the most potentially dangerous things physicians do. The patient’s request may be based on incomplete and misleading information and a misunderstanding of the likely effectiveness and safety of the medicine or how it compares to alternatives. If you prescribe a medicine, you are legally responsible for the prescribing decision.

A New Zealand physician comments: “Patients feel their drug is inferior to the one on TV. Patients with asthma now all want Symbicort® even though a long acting ß-agonist (is) not indicated for them.” (Toop, 2003). Not long afterwards, a systematic review of studies of long-acting ß-agonist showed an increase in asthma mortality (Salpeter, 2006). In some cases, doing what patients want may mean providing them with inferior care – an unnecessarily risky treatment. You may not always have the information on hand that allows you to know whether a medicine would or would not be useful for a specific patient. You can take the time to look up additional information before coming to a decision.

When advertisements blur the line between normal life and a medical problem needing treatment this is called medicalisation or disease mongering (Moynihan, 2002). Some patients may request an advertised medicine when they do not have a health problem requiring treatment.

Shifting the conversation back to the patient and the problem they are experiencing is a good technique for dealing with patient requests for advertised medicines. It is important to discuss the range of treatments available and how this advertised medicine compares to others as well as the outcome with no treatment.

Another strategy is to point out the pharmaceutical company motivation in advertising. A person who asks for an advertised medicine may be much more skeptical of other forms of consumer advertising. In some cases, they may have been convinced by indirect or disguised advertising. Where it is available, direct patients to reliable information sources (see Chapter 8 for additional information).

Box 2: Responding to patients’ requests for advertised medicines

| Suggestions on how to respond to requests: – Shift the discussion away from the medicine to the patient and his or her symptoms; – Determine the diagnosis, if there is one and whether a medicine is needed; – Explain the range of drug and non-drug treatments, including the likely outcome with no treatment; – If treatment is needed, explain your recommendation for treatment; if it is not needed, explain why not; – Explore the beliefs that have led to the request; – Discuss the role of pharmaceutical advertisers; – Refer to reliable information sources. |

Conclusion

Advertising of medicines directly to consumers strikes at the heart of interactions between patients and health professionals. At its worst, it turns the patient-doctor or patient-pharmacist relationship into a ‘health consumer-provider’ interaction, the means to obtain a desired brand. This can distract both patients and professionals and lead to unnecessary friction. In many countries, there is strong pressure from the pharmaceutical and advertising industries and media to introduce DTCA of prescription medicines. The motivation for this is clear: Advertising is very effective at stimulating sales and increasing profits by driving the consultation in a particular direction. From a public health perspective, however, there is little rationale for emotive advertising, with its promise of an easy, magical solution in the form of a glittery brand.

A person who is facing a health problem or is anxious about a family member needs to know what the available treatment options are, the pros and cons of each, including when treatment is not needed. This type of information cannot be provided by industry advertising, which primarily aims to sell a product.

In Europe, a struggle for legalisation for advertising of prescription medicines to the public ended in a resounding defeat for industry in 2002. This has now been followed by a second- wave attempt at introduction in 2006 and 2007 (Brown, 2007). This time, the ‘A’ word, ‘advertising’, goes unmentioned, and instead the discussion is of ‘medicines information’ provided by pharmaceutical companies about their products, including within public-private-partnerships. The problem with this scenario is essentially one of disguised product promotion. More independent, comparative, consumer health information is clearly needed. The pharmaceutical industry is equally clearly unable to provide this whilst fulfilling its primary duty to its shareholders.

Health professionals may find themselves affected by medicines advertising not only at a professional level in their interactions with patients, but also as citizens. DTCA of prescription medicines is highly profitable, and commercial versus public health struggles over its introduction are likely to continue. Increasingly, even where this advertising is illegal, forms of product promotion that skirt the boundaries of the law – and beyond – are also becoming more and more common. This includes commercial messages that may exaggerate disease risks (Moynihan, 2002). It can be a challenge to maintain a shared understanding of when treatment is and is not needed, and which of a range of available treatments is most appropriate. Both frank discussions with patients and public access to independent appraisals of the scientific evidence on the effectiveness and safety of medicines are part of the solution. The other part of the solution is likely to be political and regulatory.

Student exercises

- Role play of a patient-physician interaction in which a patient requests a medicine

This is a consultation in which a woman in her mid-twenties presents and requests (forcefully) that you prescribe a new weight loss pill for her. She has read about this amazing breakthrough product in a magazine and also watched it discussed on television. Apparently it has only been available in this country for a few months and some of her friends say it is great. The patient has a body mass index (BMI) of 28 and is very keen to reduce her weight for an upcoming social function (she is getting married in six weeks and wishes to go down two dress sizes to fit into her mother’s wedding dress). She takes an oral contraceptive and smokes ten cigarettes per day. Her blood pressure is 135/85 and there is a family history of hypertension.

The medicine requested, like many slimming pills, is known to raise blood pressure and pulse in some people, and has been associated with strokes and one or two unexplained deaths and unusual psychiatric symptoms. Despite having been on the market for less than three years, it has been prescribed to many hundreds of thousands of patients worldwide and the manufacturers steadfastly claim it is safe. Short-term studies of efficacy in obese patients show a modest improvement of a few kilos over diet and exercise alone after several months of treatment. There are no published long-term safety studies.

Debrief as a group on the issues such a consultation poses. What strategies can the group collectively suggest to manage these issues?

- Critical appraisal of an advertisement and comparison with independent information

Figure 7. A US advertisement for the medicine Aricept (donepezil) for Alzheimer’s disease.

(Advertisement from Woman’s Day magazine, 17 June 2003.)

- Look at the image, headlines and text.

- List the main messages in the advertisement.

- What is implied about beneficial and harmful effects? About seeking care? About the role of medicinal treatment in Alzheimer’s disease?

- List positive and negative aspects of the message in the advertisement.

- How do you think the doctor-patient relationship might be affected?

Compare the information in this advertisement to an independent assessment of donepezil and of medicines for Alzheimer’s disease. How does the message in the advertisement compare with this evaluation of the clinical trial evidence on its effects?

Go back to your list of positive and negative aspects of the advertising message:

- Having seen an evaluation of the scientific evidence on the medicine’s effects, do you have any additional comments?

- How accurately does this advertisement convey that evidence?

- What is present?

- What is missing?

3. Analysis of advertising messages about a health condition and pharmaceutical treatment

Figure 8. An advertisement for Zoloft (sertraline) for depression

(Advertisement from Shape magazine, August, 2004. )

- What is its main message about depression?

- Is self-diagnosis encouraged? Explain the basis for your answer.

- Does the advertisement allow the reader to distinguish from distress in reaction to life problems and a diagnosis of depression?

- What is implied about the rate of treatment success?

- Why is the reader told he or she should try this rather than another treatment?

- Does it suggest any alternatives to pharmacotherapy?

References

Aikin KJ, Swasy JL, Braman AC (2004). Patient and physician attitudes and behaviors associated with DTC promotion of prescription drugs – summary of FDA survey research results. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 19 November (http://www.fda.gov/cder/ddmac/Final%20Report/FRFinalExSu1119042.pdf, accessed 17 April 2009).

Anon. (2005). L’année 2004 du médicament: Innovation en panne et prises de risques. La revue Prescrire, 258:139-148.

Arnold M (2005). Changing channels. Medical Marketing and Media, 40(4):34-39.

Australian Government. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2006). Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement. Annex 2-C Pharmaceuticals.

Basara LR (1996). The impact of a direct-to-consumer prescription medication advertising campaign on new prescription volume. Drug Information Journal; 30(3):715-729.

Bell RA, Wilkes MS, Kravitz RL (2000). The educational value of consumer-targeted prescription drug print advertising. Journal of Family Practice, 49(12):1092-1098.

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A et al. (2000). For the VIGOR Study Group. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine; 343:1520-1528.

Britten N, Ukoumunne O (1997). The influence of patients’ hopes of receiving a prescription on doctors’ perceptions and the decision to prescribe: a questionnaire survey. British Medical Journal, 315:1506-1510.

Brown H (2007). Sweetening the pill. British Medical Journal, Mar; 334:664-666.

Cockburn J, Pit S (1997). Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: Patients’ expectations and doctors’ perceptions of patients’ expectations – a questionnaire study. British Medical Journal, 315:520-523.

Epstein RM, Shields CG, Franks P et al. (2007). Exploring and validating patient concerns: relation to prescribing for depression. Annals of Family Medicine, 5:21-28.

Findlay S (2001). Prescription drugs and mass media advertising. Washington D.C., National Institute of Health Care Management. September (http://www.nihcm.org/publications/prescription_drugs, accessed 17 April 2009).

Frosch DL, Krueger PM, Hornik RC et al. (2007). Creating demand for prescription drugs: a content analysis of television direct-to-consumer advertising. Annals of Family Medicine, 5:6-13.

Graham DJ, Campen D, Hui R et al. (2005). Risk of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in patients treated with cyclo-oxygenase 2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: nested case-control study. Lancet, 365:475-481.

Hansen RA. Schommer JC, Cline RR et al. (2005).The association of consumer cost-sharing and direct-to-consumer advertising with prescription drugs. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 1:139-157.

Heinrich J (2002). US Prescription Drugs. FDA Oversight of direct-to-consumer advertising has limitations. Report to Congressional Requesters. US General Accounting Office. GAO-03-177. October.

Iizuka T, Zhe Jin G (2005). Drug advertising and health habit. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series 11770 (http://www.nber.org/papers/w11770, accessed 17 April 2009).

’t Jong GW, Stricker BHC, Sturkenboom MCJM (2004). Marketing in the lay media and prescriptions of terbinafine in primary care: Dutch cohort study. British Medical Journal, 328:931.

Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD et al. (2005). Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293:1995-2002.

Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ et al. (2002). Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287:2215-20.

Marinac JS, Godfrey LA, Buchinger C et al. (2004). Attitudes of older Americans toward direct-to-consumer advertising: predictors of impact. Drug Information Journal. 38(3):301-311.

Mintzes B (1998). Blurring the boundaries: new trends in drug promotion. Health Action International (HAI-Europe), Amsterdam (http://www.haiweb.org, accessed 17 April 2009).

Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL et al. (2003). How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 169:405-412.

Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D (2002). Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease-mongering. British Medical Journal, 324:886-891.

Public Citizen Health Research Group (2003). Do not use! Rosuvastatin (Crestor) – a new but more dangerous cholesterol lowering ‘statin’ drug. Worst Pills Best Pills Newsletter, October 2003 (http://www.worstpills.org/public/crestor.cfm, accessed 17 April 2009).

Quick J, Hogerzeil HV, Rágo L et al. (2003). Ensuring ethical drug promotion – whose responsibility? Lancet, 362:747.

Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Ormiston TM et al. (2006). Meta-analysis: Effect of long-acting beta-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144:904-12.

Therapeutics Initiative (2002). Dosingle stereoisomer drugs provide value? Therapeutics Letter 45; June-September 2002 (http://www.ti.ubc.ca/pages/letter45.htm, accessed 17 April 2009).

Toop L, Richards D, Dowell T et al. (2003). Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs in New Zealand: For health or for profit. Report to the Minister of Health supporting the case for a ban on DTCA. Christchurch, University of Otago, February 2003.

Topol EJ (2004). Failing the public health – rofecoxib, Merck and the FDA. New England Journal of Medicine, 351:1707-1709.

US Food and Drug Administration (2005). CDER. Patient Information Sheet Vardenafil hydrochloride (marketed as Levitra) (http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/InfoSheets/patient/vardenafilPIS.htm, accessed 17 April 2009).

US Food and Drug Administration (2007). FDA Public Health Advisory. Tegaserod maleate (marketed as Zelnorm). March 30 (http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/tegaserod.htm, 17 April 2009).

Warshaw E, Fett DD, Bloomfield H et al. (2005). Pulse versus continuous terbinafine for onychomycosis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 53(4):578-584.

Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Tremmel J et al. (2001). Direct-to-consumer advertisements for prescription drugs: what are Americans being sold? Lancet, 358:1141-46.

World Health Organization

(1988). Ethical criteria for medicinal

drug promotion. Geneva, WHO.

Resources

1. Impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on prescribing practices

- ’t Jong GW, Stricker BHC, Sturkenboom MCJM (2004). Marketing in the lay media and prescriptions of terbinafine in primary care: Dutch cohort study. British Medical Journal 328:931.

- Zachry W.Shepherd MD, Hinich MJ et al. (2002). Relationship between direct-to-consumer advertising and physician diagnosing and prescribing. American Journal on Health-System Pharmacy 59:42–9.

- Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL et al. (2003). How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. Canadian Medical Association Journal 169:405–12.

- Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD et al. (2005). Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association; 293:1995-2002.

2. The policy debate

- Holmer AF (1999). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising builds bridges between patients and physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association 281(4):381-382.

- Calfee JA (2002). Public policy issues in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 21(2):174-193.

- Mansfield PR, Mintzes B, Richards D et al. (2005). Direct to consumer advertising – Is at the crossroads of competing pressures from industry and health needs. British Medical Journal 330: 5-6A.

- Wilkes M, Bell RA, Kravitz R ( 2000). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising: trends, impact, and implications. Health Affairs 19(2):110-128.

3. Practical regulatory issues

The US FDA’s warning and ‘untitled’ letters on promotional violations are accessible from the following page: http://www.fda.gov/cder/warn/, and are organised by year.

Two letters on television adverts found to violate regulations are listed below, as examples of the types of practical issues faced in DTCA regulation:

- Letter on Viagra (sildenafil) advert: http://www.fda.gov/cder/warn/2004/12726.pdf

Television advert: http://www.fda.gov/cder/warn/2004/12726ad.pdf

2. Letter on Seasonale (levonorgestrel/ethinylestradiol): http://www.fda.gov/cder/warn/2004/12726.pdf