|

|

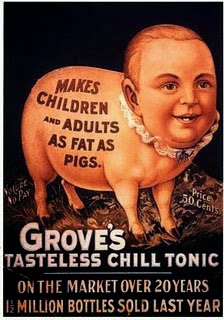

An early example of pharmaceutical promotion from

the Chico Weekly Record, 11 December, 1897. |

by TIM REED

In a perfect world, there would be a complete ban on pharmaceutical promotion and a reliance on independent information to inform therapeutic choice. Experience has taught us, however, that this is, at best, Utopian. So, in the absence of a ban, strong government regulation of pharmaceutical promotion is optimal. But even this can be unrealistic, if not impossible, in many countries (particularly in low- and middle-income countries) due to a lack of financial resources and concomitant human resources. Despite this, we must continue to work toward improving the current system of regulation, wherever it and the will to make progress are found. Better checks and balances of the pharmaceutical industry are needed and must be incorporated.

Recently, at the Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA) Philippines annual forum, I had the pleasure of suggesting a new and improved model of pharmaceutical promotion regulation to MeTA participants, who include representatives from the public, private and civil society sectors. This model, developed by the late Dr. Kumariah Balasubramaniam (former HAI Asia Pacific co-ordinator), Charles Medawar (former HAI Europe member) and me, and reviewed by HAI members, is designed with LMICs in mind.

Ideally, the model would be enshrined in primary legislation, which sets the parameters of ethical marketing. In addition to institutionalising the responsibility of the pharmaceutical industry, it would engage a broad constituency of civil society as a recognised partner in the oversight and implementation of promotional activity. The model recommends the development of a national Drug Promotions (Ethical Criteria) Act to define the meaning of pharmaceutical promotion and provide guidance on penalties for infringements, which should be based on the World Health Organization’s Ethical Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion (1988). It would also involve the appointment of three agencies to implement the regulatory system:

Office of Oversight

Who: The national Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Responsibilities:

- Act as the primary caretaker of pharmaceutical promotion oversight;

- Uphold the requirements of the Drug Promotions (Ethical Criteria) Act;

- Monitor the performance of the Designated Authority (described below);

- Set fees and fines for unethical promotion practices that fall outside recognised guidance; and

- Be the recipient of fines for infringement.

Designated Authority

Who: The pharmaceutical industry association.

Responsibilies:

- Monitor the activities of its members, according to the Drug Promotions (Ethical Criteria) Act.

Audit and Appeals Committee

Who: An independent third party, largely comprised of expert civil society, with legal mandate and power and a strong commitment to rational medicines use.

Responsiblities:

- Receive, note and refer complaints to the Office of Oversight;

- Hear appeals; and

- Recommend adjustments to policy.

Basically, then, pharmaceutical promotion activities would be identified and penalised institutionally by the pharmaceutical industry association (Designated Authority), in collaboration with the Audit and Appeals Committee. The Audit and Appeals Committee would, in turn, report them to both the Designated Authority and the Office of Oversight. This model, therefore, gives real power to civil society to control pharmaceutical promotion activity.

The model was well-received by MeTA Philippines stakeholders. In fact, they agreed to pool resources to develop a new regulatory system for pharmaceutical promotion by using the model as a springboard for discussion. Members recognised that the Philippines’ FDA, pharmaceutical industry association and expert civil society (which is well-developed, thanks to MeTA) could easily slide into the three roles identified within the model. In the coming months, the group will thrash out further details for the regulatory system and propose it to the national Ministry of Health and the Philippines FDA.

We wish MeTA Philippines great success in its attempts to improve pharmaceutical promotion regulation in the Philippines. One of the worst problems that patients who are seeking responsible prescribing of medicines in the Philippines face, after all, is the influence of the pharmaceutical industry and the collusion of healthcare professionals in unethical marketing practices. A model, like this, which legally empowers civil society as a pharmaceutical watchdog, could become a cornerstone for the development of tough controls in the Philippines. Perhaps, in the longer term, it could also become a flag

ship for regulation in other resource-poor settings.